Ladakh - the ‘Land of the High Passes’ - is among the most stunning parts of the Indian Himalayas. Wedged between Pakistan, Tibet and Xinjiang Province (China) and India’s Himachal Pradesh, it forms the eastern part of the contested state of Jammu & Kashmir. North of Leh, Ladakh’s ‘capital’, lies a far-flung and austerely beautiful enclave cradled by rugged mountains ‒ this is the Nubra Valley (often simply abbreviated to Nubra), a tuft of land on the very scalp of India.

The region actually comprises two valleys: Nubra and Shyok. Both their rivers rise amidst the remote and heavily glaciated peaks and troughs of the Karakoram Range. The Nubra joins the Shyok in ‒ as far as tourism is concerned ‒ the region’s heart near Diskit before flowing westwards into Pakistan to eventually join the mighty Indus.

Overlooking the Shyok River's broad valley, prayer flags crest a small watchtower in the stark hillside above Diskit Monastery. Local communities once prospered on an extraordinary trans-Himalayan trade which originated with the Silk Road. Comprising huge mountains, yawning valleys and vast uninhabited hinterlands, most of Ladakh’s boundaries may look almost impenetrable on a map. Yet for centuries great caravans of wool and cloth, opium, spices and skins, coral and turquoise, gold and indigo negotiated several routes and their hazardous passes mainly between Leh and Yarkand (in China). The already withering trade finally died in the late 1950s when China largely sealed its borders.

After decades of obscurity peppered with geo-political spasms ‒ it remains a sensitive border area ‒ low-key tourism has gradually injected more visitors and money into Nubra. And as increasing numbers of tourists visit Ladakh each year, more are tempted to go the extra mile and come here.

Why visit Nubra Valley?

Some of its salient features remain largely out of reach ‒ the Siachen Glacier, for example, is the world’s second longest glacier outside the polar regions, but short of a fully fledged expedition you’re unlikely to get near it. Siachen is sometimes referred to as the world’s highest (and coldest) battlefield; India and Pakistan have skirmished here at astonishing 6000m-plus altitudes, but a ceasefire has held since 2003.

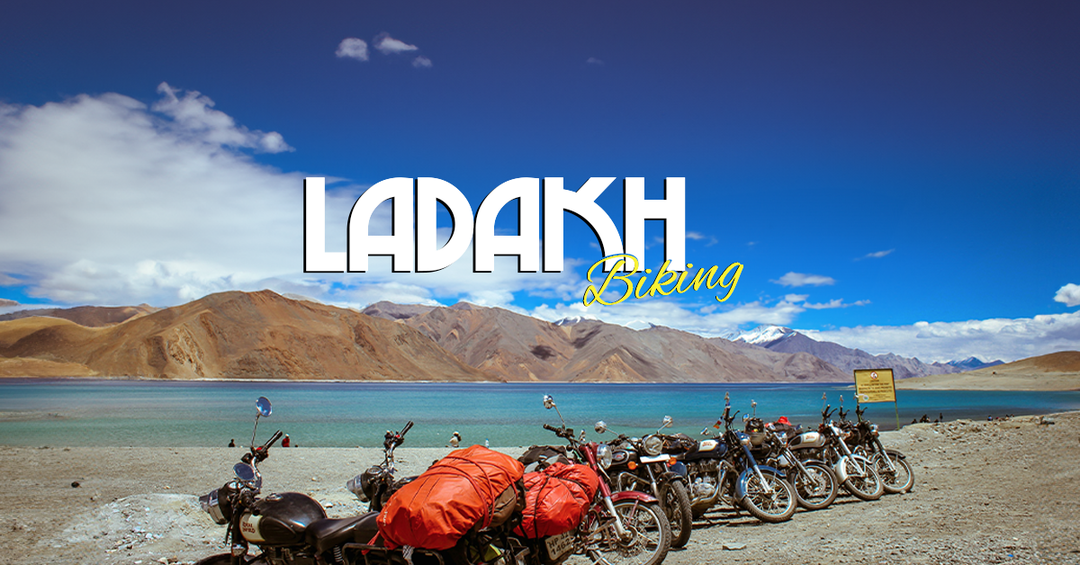

Far more relevant to today’s visitor is the journey to Nubra on what is claimed to be the world’s highest motorable road. Climbing steadily out of Leh and the Indus Valley, the road officially crosses the Khardung La pass at 5602m (18,379ft), although this height is now disputed and the accolade is probably incorrect. But don’t let the maths or contested measurements spoil what is still a great drive.

Plunging into the Shyok Valley via Khardung village, distant hamlets and their patchwork fields add a human touch to the muscular scenery and immense views. All Nubra’s settlements ‒ and there are many large, handsome homes set amidst groves of poplars and fields of barley ‒ occupy shelves of land above the rivers. A couple of ancient Buddhist monasteries, a handful of mostly feral Bactrian camels grazing a dune-like stretch of valley floor, opportunities for walking and hiking, and one long Shyok Valley drive can easily fill several days’ exploration

Crumbling chortens dot the hilllside around Ensa Monastery high above the Nubra River valley.

Diskit has become Nubra’s commercial hub, but it’s still a modest little place and more like an overgrown village. The main attraction here is Diskit Gompa, or monastery, perched high above town on a craggy spur. You can drive up here but it’s a joy to walk among the mani walls (elongated, almost artfully arranged mounds of stones engraved with Buddhist prayers and mantras) and whitewashed chortens (dome-shaped monuments housing Buddhist relics).

A little network of paths and lanes weaves among the monks’ quarters and offices to a cluster of ancient prayer halls. If you arrive by dawn you can catch the daily morning prayers ‒ chanting monks, crashing cymbals and deep horns. In another hall stands a famous statue of a protector deity brandishing the apparently mummified head and arm of a medieval Mongol soldier. Admittance to this particular hall is erratic but often easier with a Ladakhi guide. Footpaths climb up behind the monastery and past a ruined watchtower from which there are superb views of the Shyok Valley.

About 10km west of Diskit stands Hunder village. Camels can often be seen grazing on the dune-like landscape between the foot of the mountains and the braided Shyok River. It’s a pretty village, ideal for ambling, with a small roadside monastery known as Chamba. Opposite the gompa, a long mani wall indicates part of a traditional pilgrims’ route orbiting several other shrines set high in the cliffs. You can follow a lovely trail clockwise up into the hills ‒ it might look implausible but is straightforward, though you’ll need a head for heights ‒ which skirts another medieval watchtower and more terrific views.

A recently opened stretch of the Shyok Valley which descends gradually towards Pakistan is now drawing more travellers. From Diskit or Hunder the approximately 90km journey to Turtok makes a fine day-trip. It’s a gorgeous drive, the generally well-metalled road shadowing the spectacular river valley for much of the way with occasional detours through great boulder fields. And wild though it is, several scattered villages reveal a clear transformation from the mainly Buddhist Nubran heartland around Diskit to an overwhelmingly Muslim culture towards Turtok.

An elderly monk pauses in the modest prayer hall of Chamba Monastery in Hunder village in the Shyok River valley. Locals here speak Balti just as their neighbours do in the adjoining Pakistani region known as Baltistan. Several villages stand high above the main road and Turtok is among the largest and prettiest. Famed for its apricots, you might easily spend a few hours strolling through the village and across its fields to a tiny and still-maintained little gompa perched on a low ridge. There are a handful of simple guesthouses catering to its embryonic tourism; it’s a friendly but conservative place so visitors really should tread sensitively.

What Diskit is to the Shyok Valley, Sumur is to the Nubra. It’s another somewhat spread-out village with many charming houses. The main attraction here is Samstanling Gompa which stands behind and above the village at the foot of barren mountains. Built in the 1840s, it’s been considerably modernised yet still preserves an ethereal atmosphere along with two main prayer halls. Nearby and looming over the ruins of an ancient village, the atmospheric crumbling Zamskhang is now being restored. Often described as a ‘palace’ but actually a local governor’s home (probably from the 19th century when Ladakh’s royal family still resided in Leh’s palace), it’s worth a brief detour.

Continuing up the valley, you might pause at Terisha Tso, a tarn completely hidden in a bowl of jagged ridges. There’s a tiny shrine here and under clear blue skies it’s a gorgeous spot. Nearby Panamik is, for foreign tourists, more or less the end of the Nubra Valley road and its hot springs barely merit a glance. The real aim of coming here is to cross the Nubra River and head back down its western bank towards Ensa Gompa.

Perched high above the valley, a brand new access road with tight hairpin bends climbs steeply to Ensa, once probably the last word in beautifully remote Nubran monasteries. This ancient gompa is being expanded and while construction work has, for now, diminished the atmosphere, its original small hall remains intact. Located amidst a spring-fed hollow greened by dwarf willows, it’s still a ravishing spot. Two slender trails connect the gompa with the main valley road far below and, at least for the southern route, you’ll need to tread very carefully while descending the increasingly vertiginous path.

Turtok village's fields and orchards occupy a shelf of land above the Shyok River, which winds downstream towards Baltistan in Pakistan. The easiest way to visit Nubra is to organise an itinerary with an operator in your home country or, almost certainly cheaper, a travel agent in Leh. This usually includes travel by private car. The tourist season runs from about mid-June to late September, peaking in mid-July to the end of August.

Permits: First and foremost, all foreign nationals require a Protected Area Permit (PAP); apply either in person at the District Commissioner’s Office in Leh or via an authorised travel agent (plenty in Leh). The PAP, which costs 600 Indian rupees (INR), specifies where you can visit and overnight. Officially you’ll probably be listed as part of a ‘group’ (minimum two people) but in practise solo travellers have no problems. Visitors should carry multiple copies of their PAP for Nubra’s various checkpoints.

Transport: Buses to/from Leh connect Diskit (and occasionally Turtok) and Sumur but it’s far more efficient catching shared taxis to/from Leh and even between various Nubra destinations. Leh-Diskit or Sumur, about 4-5 hours, costs around INR400pp. Once in Nubra taxis can be arranged for tailored itineraries; Diskit’s taxi stand is a particularly good place to arrange this. Rates are generally fixed though out of season or with fewer visitors there’s scope to negotiate. Sample rates (for the whole vehicle) include Diskit-Turtok-Diskit day-trip INR3700, Diskit-Sumur one way INR1000. Most transport reaches and departs Nubra via the Khardung La pass; another longer and less used route takes the (almost as high) Wari La pass.

Accommodation: Small hotels, simple (often family-run) guesthouses and tented camps are plentiful. Prices do depend on the season and are often negotiable.

Also, you can create your own travel blog and share it with travellers all over the world. Start writing now!