Colombia. Drugs. Violence. Guerrillas. Death. Corruption.

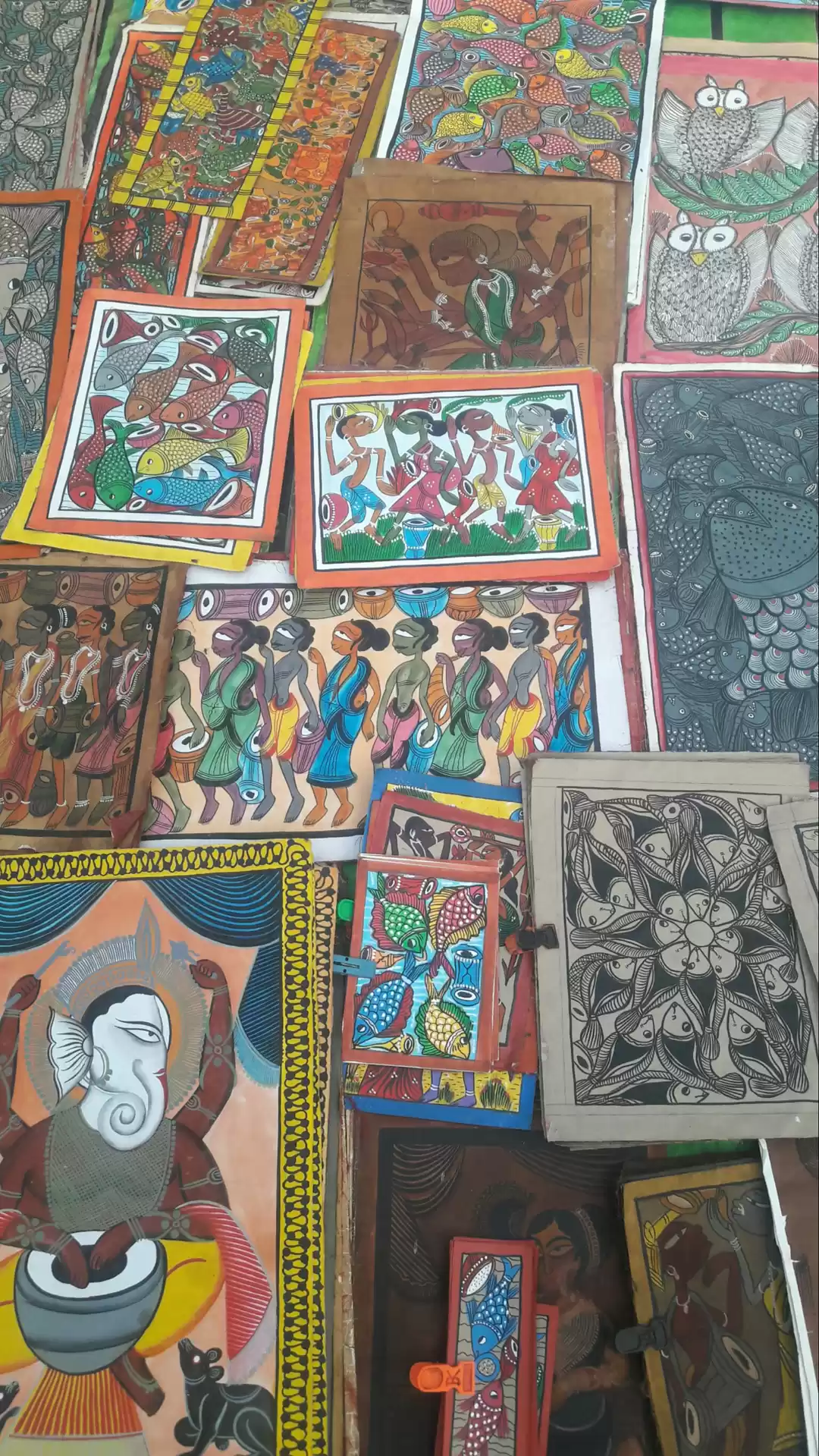

There is a common misconception within the US- and other first world countries- that these words are synonymous. I decided to write my Master’s thesis on La Violencia, or “The Violence”, in Colombia to prove that this notion was terribly false. From 1948 to 1958, the country experienced a massive genocide that could only be compared to Uganda in terms of devastating, continuous political violence. While the Conservatives and Liberals shed each other’s blood, did this mean that the Colombian people as a whole were innately predisposed to kill? Not hardly. I spent over two years of my life reading Colombian literature, non-fiction, and Political Science. I gazed upon photograph after photograph, painting after painting, trying to grasp what went on, and what Colombian identity signified. I talked to friends and strangers about their country. This was not enough.

After volunteering for a month in Managua, Nicaragua, working in the city dump, I headed south to Costa Rica with a couple of friends. Another friend met me in San Jose, Costa Rica, and we backpacked throughout the country, crossed the border into Panama, and did the same there. I wanted him to come to Colombia with me. He refused. So I went by myself. When I arrived in Bogota, I admit I was nervous. I couldn’t shake the statistics or details of La Violencia from my mind. The images I’d seen of torture, disembowelment, decapitation, and other types of violence were etched into my brain like a horrible prison tattoo. I breathed deeply, pushed those thoughts into a corner of my mind, and went about exploring the city as I would any other. All of that heinous cruelty was a thing of the past.

There was a difference, however. Bogatanos were some of the warmest, most open people I’d met on that trip. They spoke candidly about their past, about the media, the stigma placed upon them, and their daily lives. I fell in love with the city and its people, architecture, food, art, fashion, and surrounding mountain scenery. After Bogota, I continued on to Medellin, where Pablo Escobar used to reign, and Cartagena. Each place was distinct, but a common thread ran within the people. They would always remember their history, but this did not define them. Like anyone else in the world, they were living in the present, hoping for a better future.

I was never more sure of the widespread misunderstanding of Colombian people than when I was walking the streets of Bogota, each scene being absorbed, happy that my suspicions were right. While every single country in this world has problems, the media is quick to inspire fear in others in an attempt to maintain control. The vision of Colombia has been greatly misconstrued in many foreigners’ eyes, and this perspective couldn’t be further from the truth.