“The world is a book and those who do not travel read only one page-” thus spake the Augustine of Hippo; and since I am a voracious reader, I decided to read a few more pages this year (August 2017). This reading took me up the long, winding roads of the greater Himalayas, and I found myself wandering in the 'land of high passes': Ladakh . While taking one of the lesser explored trails into far north western part of Ladakh, we ended up in the village of Turtuk. Nestled amidst the towering peaks of the Karakoram, this village was once a part of Gilgit-Baltistan region.

When I reached, I found it sitting smug under the warm August sun, wrapped in the thoughts of its glorious past.

Taken over by Pakistan post -independence, Turtuk, which is hardly 10 km from the Line Of Control (LOC), became a part of India during the Indo-Pak war of 1971 under the able leadership of Major Chewang Rinchen. Settled in the shadow of the famous K2 peak that falls across the LOC, this village has the river Shyok flowing beside it. Its greenery came as a relief to our eyes that were sore after hours of gazing at the black tarmac road, boulders, and white sand on all sides, without any vegetation.

The Shyok river which gives company till Turtuk, flows across the LOC and meets the Indus. Shyok, which means "Death" in Uyghur, was named thus as it frequently floods its sides, cutting banks causing soil erosion. Many times the river has wiped out entire villages often forcing villagers to move away and seek home elsewhere. The Shyok has not quietened with time and with an increased volume during the summer, it is impossible to cross the river. People living in villages such as Hunder and Utmaru are forced to use boats known as bips, for crossing it at remote places where there are no bridges.

Sand on my road.... The road to Turtuk is mostly barren with no habitation except a few patches of green thorny shrubs, white sand and boulders in all colours, shapes, and sizes. A Cold Desert indeed.

Turtuk, once part of the inland trade route (the silk route) for merchants travelling through the Karakoram ranges, was likely to have been an important trading post linked with Tibet, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. However, little recorded history is available of those days and what we now see has been shaped more by the 1971 war and events thereof. With the closing down of borders in 1971 and the ancient trade routes sealed, the economic lifeline was cut off, choking Turtuk and the other border villages.

The United Province of Baltistan, divided by recent borders. Interestingly, the area of Ladakh (of which Turtuk and adjoining areas are a part) has seen many partitions before. It started in 9th century CE when it was separated from the Tibetan empire by Beg Manthal of the Yabgo dynasty who conquered Khaplu. Later, in 1834 CE, the Dogra rulers from Jammu annexed it and made it a part of Jammu and Kashmir. Then in 1947, the Indian subcontinent underwent partition, and Baltistan was taken over by Pakistan. Finally in 1971, the Indian army took back the control of Turtuk and three other villages.

Baltistan once was a separate kingdom, and a Central Asian tribe named the Yabgo dynasty, controlled the united province from Chinese Turkistan. Among the rulers of the western Turkistan, the Yabgo surname belonged to the leader of the Gaz tribes whose kingdom extended from Afghanistan to Turkistan. The Yabgo reign in Baltistan started from around 800 CE, when Beg Manthal, the 10th descendant of Prince Tung (he started the Gaz dynasty), came from Yarkhand (a part of modern China) and conquered Khaplu. The dynasty's reign lasted until 1834 CE when Ladakh was annexed by the Dogra rulers of Jammu. The Yabgo dynasty were patrons of art, poetry, and literature, which flourished under their long rule over the region.

The family tree of the Yabgo dynasty prepared by the current 'king' Yabgo Mohammed Kacho with help from Indian Army.

The descendants of the Yabgo dynasty still live in Turtuk and the family is considered as rulers by the villagers. The 'king' Yabgo Mohammed Kacho, a rather down to earth and soft spoken gentleman, receives all those that visit his former summer home that now serves as a museum with great warmth. Some of his family members remain on the other side of LOC, as do many family members of other villagers. Along with this pain, the villagers harbour a regret that the Indian army did not take over the entire Baltistan that fateful night during the war.

Turtuk reeled under two long decades of mistrust arising from a sense of mixed emotions of losing close family members to Pakistan, and add to it the apathy and neglect shown by the Indian government towards these border villages. Finally in 1999, Lt Gen Arjun Ray, who was then the Commander of 14 Corps, started ‘Operation Sadbhavna,’ which aimed at reviving a positive civil-military relationship. Under this operation, the army undertook many projects that ranged from building schools, developing infrastructure, to establishing computer and other vocational training centres, poultry farms, programs aimed at women empowerment, providing telephone connections, free medical services, and a daily bus service. Today, for the people of Turtuk it is "upar Allah, niche Indian Army." Turtuk stands as a shining example of how things can work out amicably, when both sides are willing and able to appreciate each others efforts.

The current 'king' Mohammed Kacho of the Yabgo dynasty tells us the story of the former glory of his ancestors, of the fateful night when they became Indians, and how the Indian army is the best thing to have happened to the villagers. He categorically said that while politicians are the same corrupt players on all sides of the borders, it is the Indian army that stood by them at all times. His former palace was almost entirely looted and destroyed by the Pakistan army because his father had filed a case in the Lahore court against them for illegal occupation. Almost nothing remains of their former wealth and the only evidences seen are in the form of dusty artefacts that are a part of the museum.

Located at an altitude of 9846 feet, the village of Turtuk is inhabited by the Balti people of Tibetan origin. Once one crosses the Hunder area and nears the Balti zone, everything changes drastically: the landscape, physical features of the locals, clothing, language, and culture which is markedly different from the rest of the people in Ladakh. The Balti women are seen wearing colourful floral prints that stand out in contrast amidst the stark mountains all around.

The villagers in Turtuk. The women are still not so open to being photographed, so didn't take their pictures. Extremely hospitable, the villagers are always ready to talk and help.

Turtuk being warmer, the villagers are able to cultivate two crops in a year. Barley, wheat, buckwheat, peas, spinach, pulses, beans, and mustard are widely grown. Among livestock that provides milk, meat, and wool, are the dzos (hybrid of yak and cow), goats, dzomos and sheep. Fruit cultivation is another widespread practice seen in all these border villages and the little gardens abound in apricots, walnuts and few apples that help to augment the villagers' incomes. Interestingly, there is a Tsarma apricot juice factory in Turtuk that sells pitted and pressed apricot juice. Since Turtuk is a strategic military outpost, it was closed to outsiders (even other Indians), until 2010, when the locals weary of isolation and looking to increase their meagre incomes petitioned for the beautiful valley to open up. As tourists slowly started trickling in, albeit armed with permits, tourism as an industry started evolving bringing in the much needed cash.

We were offered these apricots by a lady who was standing in her garden as we walked towards the museum. She plucked them from a tree, washed them in a flowing stream, and offered them to us. As we bit into them we realised we were having the best apricots we have ever had. Juicy and sweet, they were absolutely delicious, and I can guarantee that I have never found such wonderful apricots in the markets of NCR!

Fruit laden trees and vines: apricots and grapes. The villagers sell their fruit and crop produce in the local markets and to the army, and sometimes travel to Nubra, Hunder and Diskit to sell their fruits.

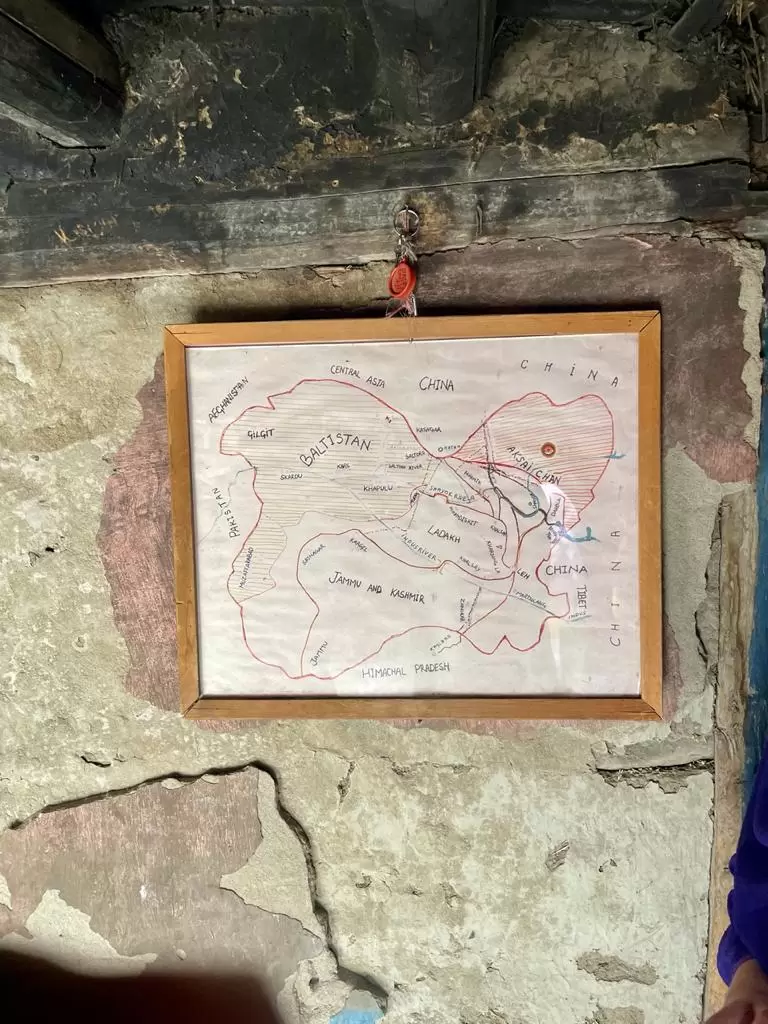

A hand painted map for the travellers in Turtuk

Baltistan was predominantly a Buddhist region, which changed when Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, a poet from Iran and an Islamic scholar, arrived there in the 13th century CE. An old mosque near the memorial of Captain Haneef Uddin (Kargil war hero) still stands in the old part of Turtuk. While its exact period of construction remains unknown, it was first renovated in 1690 CE. The mosque has a blend of Buddhist designs, swastikas, and Iranian motifs. Turtuk villagers are mostly Muslims, unlike other parts of the Nubra valley, and 70% of them follow the Nurbakhshi school of Sufi Islam.

The village blacksmith's shop that we came across right at the beginning of our exploration also doubles up as a place for the village men to meet and exchange gossip.

As we walked through the narrow cobbled lanes of the village, we marvelled at the wooden, gaily painted houses that were huddled together, almost as if they wished to escape the winter cold. Some houses showed old carvings on them. As we explored the village further, following the hand-painted map, we found a wooden house that was larger than the other houses and it turned out to be the museum and the king's former summer palace. At the entrance gate there was a large wooden eagle hanging, which symbolised the ‘saviour’. As we looked at the house (it certainly didn't look like a palace), we suddenly noticed the old wooden doors and the wooden carved cornices that still held flaky remnants of colours on them, and it seemed as if these old walls were telling us a story of a kingdom long lost.

The wooden eagle on the gate of the former summer palace

Inside the summer palace courtyard

On the palace terrace, there is a vineyard !

Some artefacts displayed in the family museum.

The remnants of 'king' Kacho Mohammad Khan's family wealth are seen in his own private museum in the summer palace. The collection includes coins, old metal and earthen pots, silver ink containers, shields, arrows used in war, lapis lazuli encrusted sword, paintings, clothes, headgear, footwear, family record books, leopard traps,stuffed heads of hunted animals, along with a donation box for the visitors. The current 'king,' who is a writer and lover of books, earns his daily bread by selling fruits and vegetables to the Indian army. He is also likely to be the last king of his dynasty that once ruled Baltistan for more than 1000 years. His only son is more interested in doing business than performing the role of a non-functional king of a non-existent kingdom.

Turtuk, a charming high altitude border village, with its hospitable and friendly people, has steadfastly refused to take part in any attempts at radicalisation, and are solely focused towards creating a cordial atmosphere. Their patience and efforts have borne fruit, and today tourists are coming in from all parts of the world to Turtuk and returning with wonderful memories of love and affection received from the villagers. With hopes of a better tomorrow, Turtuk can now sit smug and revel in the stories of its past glory.