In Chile's remote Cape Horn archipelago travel writer Brendan Harding meets one woman as she faces the end of her culture

For Cristina Calderón, the last full-blooded remnant of the Yaghan people who have called this end-of-the-world outpost on Chile's Cape Horn their home for over 10,000 years, it is perhaps already too late. Flanked by four of her family members inside the wooden 'kipakar' (the women's house where Yaghan crafts are produced and sold) Cristina's face is set with the fierce resolution of one whose fate is already sealed and accepted.

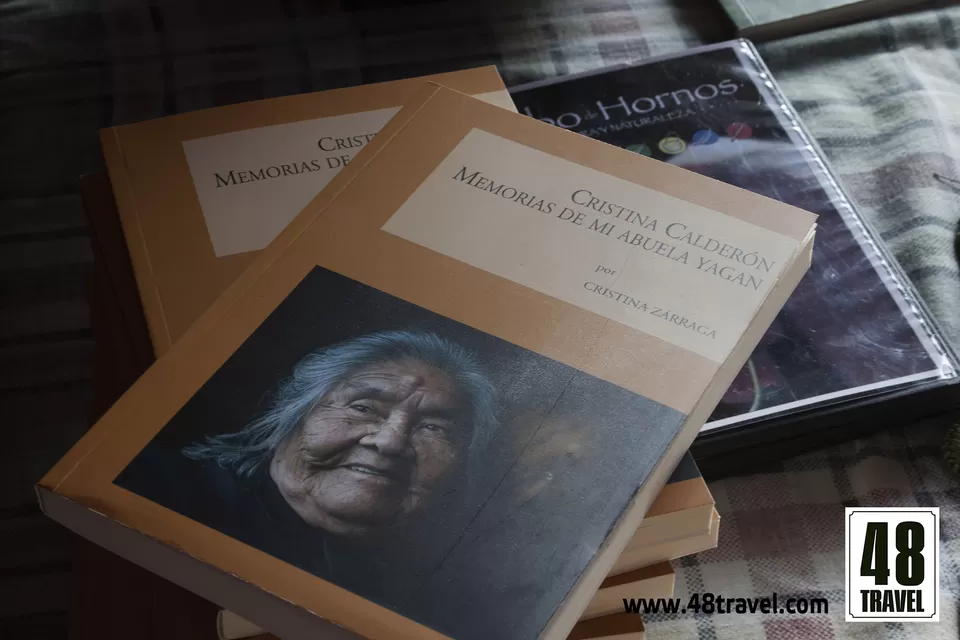

She is a handsome woman, grandmotherly, the soft lines which map her face only serve to add the appearance of wisdom to this aesthetic as she nears the turning of her 89th year. Cristina, the last native speaker of the Yaghan language, sits quietly with her head tilted back at an angle, spectacles perched on the end of her nose, hands crossed serenely on her lap, her straight grey hair captured in strands by the low Chilean sub-Antarctic sunlight flooding through the window behind her.

Beyond the window lies the mirror-calm waters of the Beagle Channel and the distant snow-covered mountains of Tierra del Fuego; the only ones who truly know Cristina's story and the story of the Yaghan people whose blood still flows through her veins, and the lands of her ancestors.

Around her are her children and grandchildren; Julia, Claudia, Macarena and Martin. On a table before her are the handicrafts of the Yaghan, the knowledge of their creation handed down from generation to generation: whale bone harpoons, sea-shell jewellery; and miniature canoes, crafted from wood and tree bark bearing memories of the original vessels which carried the Yaghan from island to island in these frigid southern waters, as they hunted, fished and gathered in their nomadic lifestyle rooted to the earth.

There is also an assortment of delicate reed-made baskets of differing sizes and styles. "These are the baskets of the Yaghan," Cristina explained, "they were a unique tool we used to gather what we needed from the land and sea. This one was for collecting berries," she said pointing to a tightly woven replica, "and this for gathering shellfish from the shore." There is no hint of remorse in her face only a stoicism and acceptance of what things once were, now are and soon will be. "The reed was once everywhere and easy to gather, now we have to travel four to five days away to collect the bundles, because of climate change," she explains, "the others have already been burned by the sun."

It is already April, late Autumn in the far south. "In the past, by March, we had snow and rain but not anymore. We used to have a festival to celebrate this time, the coming of the snow, but now it's the festival of the mud." She does not smile at the joke she just made, and neither do her family.

The ramshackle community of wooden houses whose yards are littered with abandoned cars, set on the edge of the town of Puerto Williams - the southernmost 'city' in the world, whose population is less than 3,000 - is home to between seventy and eighty Yaghan descendents, including those who have already left. When asked why do the ancestors of the Yaghan leave Puerto Williams, Cristina answers simply, "They create families and move to other places. We don't have much help from the government, none of us even own a piece of land."

'...never taking more than they needed...'

The Yaghan, the original peoples who migrated here against all the odds, who learned to survive in the harshness of the landscape with little or no clothing, coating their bodies with whale and seal fat to protect against the numbing environment, the people who learned to survive on what they found, never taking more than they needed or destroying their bountiful landscape are now denied possession of the very lands they pioneered.

The people who knew every bay and cove, whose very lives depended on their skill and knowledge of the waters surrounding their world are now no longer permitted to take their boats on the channels and inlets without licence and registration and the installation of costly navigational aids. These are the people whose campfires as they burned on the shorelines at night gave the name to the land of Tierra del Fuego, the Land of Fire. Their existence was witnessed by those who navigated their waters; Magellan, Drake, Le Maire, Schouten, Weddell, Cook, Darwin, and the Dutch Admiral Jacob l'Hermite, the first European to make contact with the Yaghan in 1624. In 1830 the name of the Yaghan became widely known to the British general public for the first time when Captain Robert FitzRoy, commanding the first expedition of the vessel the 'HMS Beagle', returned four Yaghan natives to London aboard his ship. Having believed one of his boats stolen by the Yaghan - this was never verified - FitzRoy took four young Yaghans hostage. Unable to master their Yaghan names FitzRoy and his crew imposed their own upon the four: a girl, Yokcushly was named Fuegia Basket, and three young men, Elleparu (York Minster), Orundellico (Jemmy Button), and another named Boat Memory who died of small pox on arrival in England and whose Yaghan name was never recorded.

The surviving three became celebrities in their imposed exile. They learned the English tongue, the manners of gentlemen, were introduced to Christianity, and were even presented to his Majesty King William IV and Queen Adelaide before being returned to their native homeland in 1831 where it was hoped they would aid in spreading their newly found manners and religion among their fellow Yaghan. However, on return the three quickly reverted to their native manner and custom, a trait which heavily influenced the young scientist and naturalist Charles Darwin on a later encounter with the Yaghan. With the colonisation of the Yaghan native lands their population was decimated due to illnesses to which they possessed no resistance, and also due to the Yaghans having no concept of property and being captured and killed having 'stolen' the new colonisers livestock.

Today in Puerto Williams Cristiana Calderón, sitting resolutely in the dim light of the dwindling community's 'Kipakar', is the last living testament to a pure lineage which had survived for millennia. Despite the fact that Martin, one of the family members at her side, his brother José Manuel (affectionately known as Poppy), and the other members of Cristiana's extended family are doing their best to preserve what they can of the Yaghan way of life and the Yaghan language the odds are stacked heavily against them.

I ask Cristina one last question before I leave her tiny community at the end of the earth; does she and her family feel resentment towards those who have led to the Yaghans demise? Her expression remains unchanged; resolute, inward, almost spiritual. "No," she answers simply, "resentment is a negative thing and it does no good to carry that negativity inside you no matter what may happen in life."