Intro

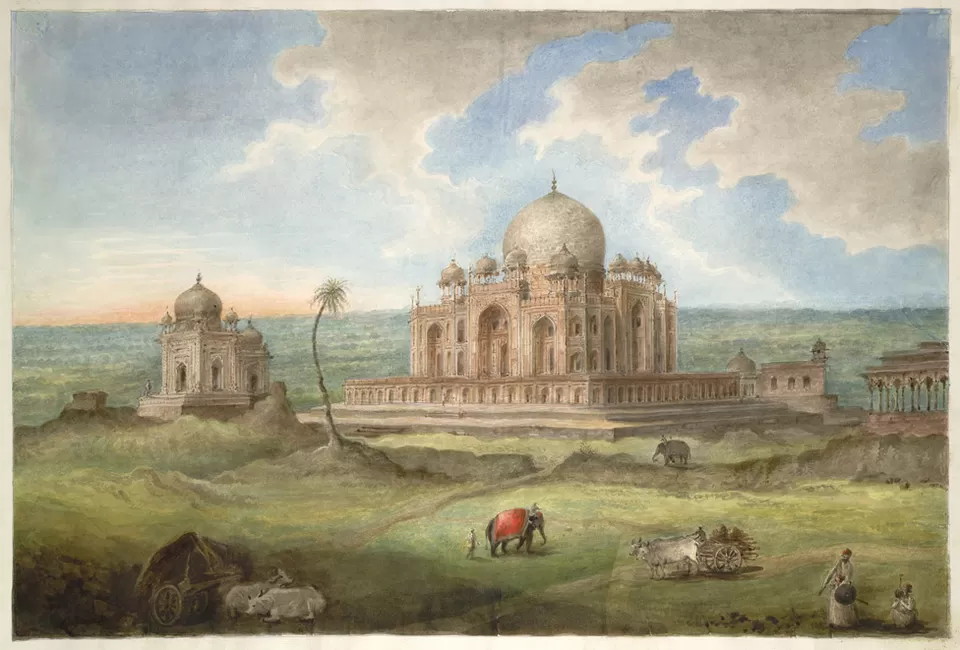

If someone ever asks me if they could only visit one location in Delhi, my answer will undoubtedly be Humayun's tomb. This monument, a sumptuous tomb in the heart of a char bagh garden, is a symbol of love and an architectural wonder that begins a tradition of rulers being buried in a paradise tomb in India. This mausoleum was the foundation stone for Indo-Persian Mughal architecture, culminating in the Taj Mahal.

Let us travel back to when the Mughals were only establishing their influence in India. Humayun was the second Mughal emperor of the famous lineage of Amir Timur and Genghis Khan. After Humayun died in 1556, his principal consort, empress Bega Begum, was devastated by the death of her husband. Their son Akbar, who was just 13 years old then, was enthroned as king and the next heir to the throne. Later in 1558, she chose to demonstrate how strong and ambitious Empress Bega Begum was.

She decided to build a memorial for her husband, the first garden-tomb of the Indian sub-continent that would serve as an inspiration for coming generations of Mughal architecture in India. Humayun's tomb was commissioned under Persian architect Mirak Mirza Ghiyas and his son, Sayyid Muhammad. It required around 1.5 million Indian rupees to construct in 1558.

Time and the tomb's fate

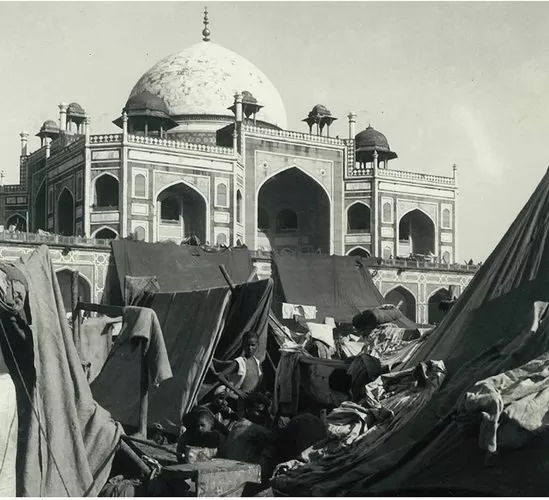

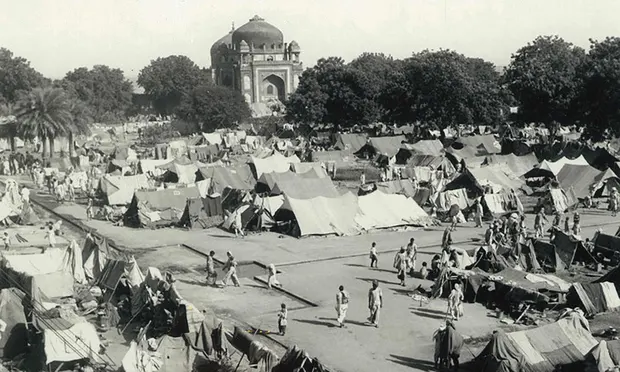

This tomb has seen a lot throughout the years, from a wealthy mausoleum to ruins to rehabilitation. It has seen everything. During the tragic partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, this mausoleum and its gardens functioned as a refugee camp.

William Finch, an English trader who visited the tomb in 1611, recalls the exquisite interior decoration of the middle chamber (in comparison to the sparse look today). He recounts the existence of magnificent carpets, as well as a shamiana, a tiny tent over the cenotaph draped in a pristine white sheet and containing copies of the Quran in front, as well as Humayun's sword, hat, and shoes.

The fate of the once-famous Charbagh (Four-gardens), which consisted of four squares connected by four promenades extending from a central reflecting pool. It grew across 13 hectares around the monument and was modified several times after its erection. The capital had already transferred to Agra in 1556, and the Mughals' collapse hastened the degradation of the monument and its features, since the costly care of the garden proved unfeasible. The previously beautiful gardens had been replaced by the vegetable gardens of residents who had lived within the walled area by the early 18th century.

After the insurrection of 1857, the final emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was caught and exiled, and the British government took control of all Mughal estates in India.

Later, on Lord Curzon's instructions, the tomb and gardens were repaired, which took six years from 1903 to 1909.

Then followed the dreadful division of 1947, which led to 2 million deaths and 20 million displaced people. This mausoleum then functioned as a temporary residence for immigrants from Pakistan to India.

Later in the twentieth century, the mausoleum was restored to its former splendor by the Aga Khan Trust, with money from the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and collaboration from the Archaeological Survey of India.

Why I called it a Mughal dormitory

In Delhi, where do the majority of Mughal emperors, princes, and princesses sleep? The solution may be found in the vaults of Humayun's Tomb, which was lovingly constructed by the emperor's first wife, Haji Begum. Among those buried here are Akbar's mother, Hamida Bano Begum; Shah Jahan's heir apparent, Dara Shikoh; Aurangzeb's once-beloved son, Azam Shah; the dandy Jahandar Shah and his murderer Farrukhsiyar; Ahmed Shah and Alamgir-II.

There are many others of lesser renown, some without inscriptions, nestled inside the folds of their ancestor Humayun's tomb. It's an odd sensation to see beds laid out on a summer night, with the benevolent emperor resting in splendor among many of them who waded to the throne by the blood of their family. The final rituals of assassinated princes were regularly observed, and they were buried in the family cemetery. Dara Shikoh, for example, was denied the ceremonial funeral bath by his austere brother Aurangzeb before getting buried.

Notable Structures in the complex