A tailor usually takes pride over the fine cut, the thread even, but Saheb gloated over the fabric.

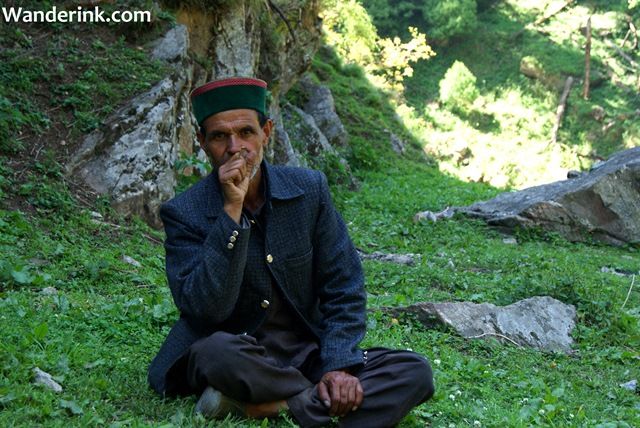

“This kind of wool you get only in the Garhwal region.” He said running his fingers fondly down the braid, eyes urging me to do the same. He took a long pull from his beedi through cupped palms before continuing.

“The place has to be beautiful if you want something as pretty as this.” I had found Saheb, the tailor of Taluka, the last motorable point from where you begin the trek to the Har Ki Dun valley, gazing out at the gushing Supin River from under a Moru oak tree. Saheb came here first as a young groom many decades ago and stayed on.

“I just could not go away from this lovely land.” He said nodding at the Supin with the subtlety of stating the obvious.

The lure of the Garhwal is an old story. Two centuries before Saheb, Captain Thomas Skinner, British soldier and author, wrote in Excursions in India (1832), “I have beheld all the celebrated scenery of Europe, which poets and painters have immortalised and of which all the tourists in the world are enamoured; but I have seen it surpassed in these unfrequented and almost unseen region.” He had made exploratory forays into little-known mountainous areas surrounding Dehradun where he was stationed with the 31st Regiment. ‘A thrilling region of thick ribbed ice,’ was how Skinner described the area.

The thrills and the thick ribbed ice are plenty once you reach the Har Ki Dun valley, a two-day trek from Taluka. The moderate-grade trek first passes through Gangar tucked away from the track on the other side of the Supin before a steep gradient lands you in Osla, a quaint village rolling down a mountainside in disarrayed haste. There are snotty bids for ‘toffee’ even before you reach the village square – the scrupulously clean area around the main temple. The experienced, elder ones have worked out an ingenious racket: they flash their cutest smile at you making you almost yearn for a photograph. Once you have your camera out, their one hand will go over their faces while the other will be stretched out for the bribe. The street-smart is playful and harmless at present but I did hear stories of it getting out of hand.

Much as the views from Osla are mesmerising – I sat with my cuppa gazing at the mountains forever – you cannot help but notice the recently shaven tracts of land all around, cleared for agriculture or for construction. Uttarakhand, along with neighbour Himachal Pradesh, is among the states that fall under ‘Special Category Status’ owing to factors like low resource base, difficult terrains and low population density. However this status does not seem to address – or even try to – the rapidly changing ground reality: bursting population density, lack of education and sanitation and basic infrastructure. Even sensitisation towards the needs of burgeoning tourism traffic. There is systematic and rampant deforestation – as wood is the primary source of firewood, furniture and construction – which has to be checked if the hills are to remain verdant, the trails pristine and prevent repeat episodes of last year’s devastation of the region.

The Supin and the Rupin are the two feeder streams which come together as the Tons River in Naitwar. The Tons is an important tributary of the Yamuna. While the catchment area of the Tons is one of the richest and densest forests in the western Himalaya, those of the Supin is not shorn of diverse flora either. Trekking along the Supin takes you through a lush bank teeming with deodars, birches, fir, pine and oak trees.

Pack mules are an important income source for the locals who hire them out @ Rs 1000 per day to trek organisers and guides.

Saheb, the tailor from Taluka, enjoys a beedi while taking a break. What constitutes the first day’s trek for us – 12 kilometres to Osla – is everyday for Saheb.

Water from these hollow shoots appended onto rocky outcrops is generally safe to drink from; it is also cleaner than gulping down directly from the stream or from under the waterfall.

Osla, like most of the Himalayan villages, is facing a huge population explosion; in its struggle to find more space it is scattering in all directions including precariously upwards cutting down the very trees holding together the mountains looming over them.

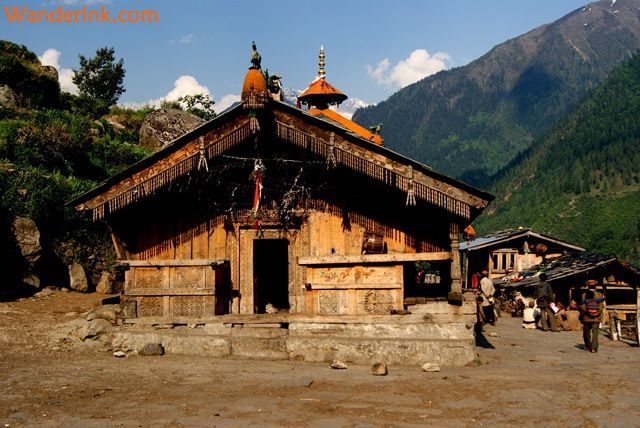

The evening sun washes over the Someshwar Temple, the area around which is also the village square. Earlier travellers attest that the temple used to worship Duryodhana (several ancient texts too say that Duryodhana was a well-loved king who ruled supreme in the Har Ki Dun valley of Uttarakhand) even though the villagers deny it. A few kilometres out of the village however is a temple where an occasional goat is sacrificed. My visit to the temple did not yield much information as there was a young boy, the priest’s assistant, apparently, whose only concept of communication was extrication of toffees from travellers through snarls and glib gestures.

At first sight the ferocious looking designer leash looked to be the handiwork of a vain owner. But these sharp-toothed collars are to protect the shepherd dogs from tiger and bear attacks. This one here – called Shera (meaning ‘tiger’) – had been mauled by tigers on two occasions near the Jaundhar Glacier, a few hours from Har Ki Dun. The collar, though a crimping discomfiture, has been the lifesaver.

Forget hospital, Osla does not have a simple clinic/dispensary even. Within a few minutes of us checking into the rest house, villagers began trickling in with complaints of fever, toothache and acidity – the three most common ailments I encountered during my stay here. Paracetamols were shared generously – but with the adults. A lady came with a wailing baby who had to be sent back with the little one still wailing. Ground realities can oftentimes be a bummer.

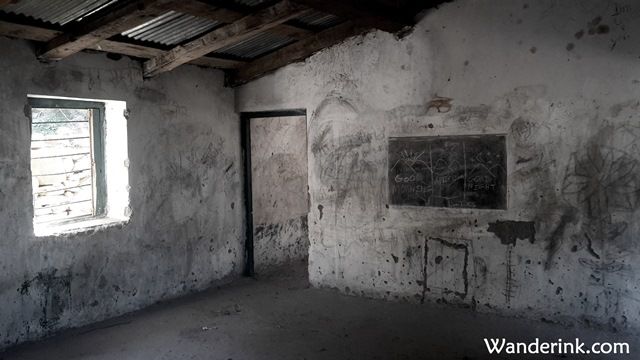

Surprisingly there was a pretty decent school building in the village but unsurprisingly it was abandoned, unused for several months. “There is a teacher who draws a regular monthly income but never bothers to come,” I was told by a local. Anybody reading this post who has access to the current state chief minister Mr Harish Rawat, kindly ask him to take note.