It’s that time of the year when the leaves change color in this part of the world. In another part of the world, the autumn winds usher in the season of festivities. With autumn comes the kaash phool, the harbingers of Durga Puja, my biggest festival of the year. But while folks back home plunge headfirst into the revelry, I go about navigating the crowds of the subway, eating my sandwich sitting on a park bench. Amid this daily grind, the mind inevitably wanders to endearing thoughts of puja in my beloved Calcutta.

Ask any discerning Bengali to throw some light on Durga Puja; they will gladly dispense with the job at hand and embark on a discourse. Everyone knows this by heart – how every year, Ma Durga embarks on her journey to earth from the heavenly abode of Kailash. She is accompanied in her earthly sojourn by her four children – the golden complexioned Lakshmi, the muse of every Indian artist Saraswati, the elephant headed Ganesh and the suave god of war Kartik. Ma Durga is mother to all earth dwellers, combining in herself the prowess of all mothers on earth. She comes every year to her followers and grants them their wishes, forgives them of their sins, wipes away their sufferings and brings peace and prosperity on earth. This has been the custom since time immemorial and will continue to be for eons to come.

The origins of Durga Puja can be traced to the first baro-yaari puja, sometime in the late 18th century, organised by twelve friends of Guptipara in Hoogly, West Bengal. They collaborated and collected contributions from local residents to conduct the first community puja in Bengal. What had thus begun with baro-yaari puja has given way to theme puja, with every puja pandal striving to depict a particular theme in the pandal decorations. The outcome has been the creation of magnificently crafted pandals and embellishments, avant-garde works of art.

However, it’s the Bengalis’ unfathomable preoccupation with this festival that belies all rationale. On Dashami, grief-stricken worshipers wipe tears from their eyes as the goddess departs for immersion. Some even claim to have seen the goddess silently weeping on a few occasions. Indeed, the sculptors of Kumartoli are known to infuse a certain variety of oil in the clay that starts melting at the end of 5 days, giving her a forlorn look. Most people are aware of this ‘closely guarded secret’, nevertheless everybody loves to believe in the myth. After all, it is Bengal, where Durga Puja is synonymous with faith, festivity and frenzy, even ecstasy and euphoria and borders dangerously on the fringes of obsession.

Likewise, there is little rationale behind all work in government offices, municipalities, banks, doctors’ chambers and courts of law coming to a grinding halt during pujo. These are probably the only 5 days of the year when even cricket takes a backseat and puja celebrations unanimously feature as headlines everywhere. There is no rhyme or reason behind such aberrations; the whole of Bengal simply loves to get soaked in this incurable eccentricity.

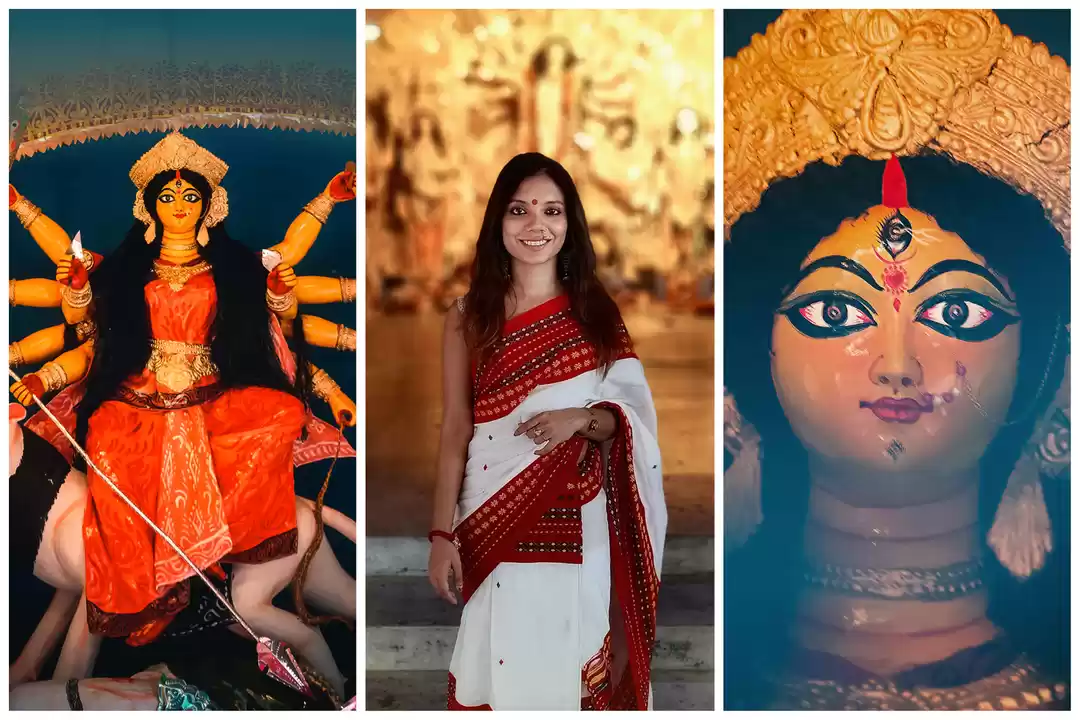

My tryst with overseas Durga puja happens out of a desperation to get one glimpse of the goddess. Braving the impending chill I don my favorite red saree, sit through puja packed into a weekend and pay through the nose to gorge on savories. But the heart knows that all this is a far-cry from the bonhomie and fervor of celebrations in my homeland. Many a flirtatious glance is exchanged and many a handful of sandesh is crammed into one another’s mouth. A cloud of festivity hangs in the air as tangible as the delectable aroma from cooking pots. People from all strata of the society queue up at the pandals, rubbing spines with one another, oblivious to the social order that differentiates them for the remaining 360 days of the year. Perhaps herein lies the tour de force of the most revered festival in the life of a Bengali.