Rakcham is only about 10km from Chitkul and just about the same distance from Sangla. The best part about Rakcham is that despite its proximity to the two well-known tourist destinations, it’s relatively deserted. Nestled in pine forests and with the Baspa flowing close by, it’s heaven for solitude-seekers.

From what I could figure out during our brief stay, there are still only a couple of hotels in Rakcham. One is Rupin River View, which is closer to Chitkul. The other is Apple Pie, which is further towards Sangla. If rivers attract you, it’s better to put up in Rupin River View because it’s level with the river valley. Apple Pie is more uphill and the river valley is deep enough to be probably called a gorge at that point.

The beauty of Apple Pie lies in the pines surrounding it. Blue, chilgoza, chir — all kinds of Himalayan pines jostle for space to find a toehold in the slopes leading up from or down to the tiny hill hamlet. When we reached Apple Pie, there was probably no other tourist staying there, though we later saw a foreigner (probably European) trio out on a walk nearby and the next morning, we saw an elderly Indian couple having breakfast in the small dining space downstairs.

Our first-floor room had two huge windows — one of them, with a broad windowsill, overlooked the pine-swathed mountains topped with the last of the season’s snow. I spent the entire afternoon sitting on it, until it grew dark. And Eti discovered just in the nick of time that the other window was offering the view to one of the finest sunsets I have been able to catch in the Himalayas so far.

As night fell, the only lights to be seen were those of Sangla, far away in the valley. The lights of the hotel were dim — just about strong enough for practical purposes but weak enough to leave the mood of solitude undisturbed.

Thanks to the thick foliage all around, there was no dearth of wildlife. The walls of our bedroom and the bathroom were occupied by four different types of moths. There was nothing to be heard except for the sounds of nature — the gurgling of water, chirping of crickets, rustling of leaves or the whistling of the wind. Add to that the scent of the pines... Life couldn’t have been better.

=========================================================

The next morning, we went out for a short walk after breakfast. Shrubs of wild roses and Himalayan indigo grew nearby. Pinecones lay everywhere. Eti started collecting some of the cones, which she said were different from the ones they have in Meghalaya. She chose a couple for me too and we managed to carry the fragile cones all the way to our respective homes in Kolkata and Meghalaya by flight.

Unlike our hotel in Kalpa, which was isolated on a hilltop, Apple Pie was surrounded by wooden Kinnauri dwellings. Some were in fact a mix of cement, wood and glass, and most had corrugated tin roofs.

One house was particularly interesting. It looked like a ramshackle one-room wooden structure resting on rickety wooden stilts. A narrow little wooden staircase led up to the front door from a little iron gate fastened to two short cement pillars on each side, only about a foot in breadth. After that, the boundary line had been marked in the traditional style — by a wall of loose rocks placed in a way that they stick together without any fastener like cement (though about a 2ftx2ft part of the wall at the bottom had been cemented). The corrugated tin roof looked sparkling new, but only one side of the triangular wall below the roof was covered by wooden planks. Several other planks were lying on the ground nearby.

Evidently, the house was still being built, but it looked like it would fall apart any moment. But amid all this, proudly resting in a corner of the compound was a Tata Sky dish antenna (a direct-to-home television service provider in India). It seemed that the pieces of the ‘development’ pie were reaching all corners of the country. But somehow the dish antenna, which must be a prize possession of the owner, looked awkwardly out of place in the pristine surroundings.

We came across a few local residents while out on the walk. Though for daily purposes, many Kinnauris have given up their traditional attires for more convenient Western clothes, they have certainly held on to the ‘thepang’, the woollen cap with the green flap that is a popular souvenir for tourists too. Its shape is similar to the Kullu cap, which is usually embroidered in colourful geometric patterns. Both men and women wear it.

The traditional attire is still worn at festivals and special occasions though. Here is what Shiva Chandra Bajpai writes in ‘Kinnaur in the Himalayas: Mythology to Modernity’ about traditional Kinnauri clothes:

“The men wear woollen shirts chamu-kurti, a long coat (chhuba), woollen pyjamas (chamu sutan) mostly of grey colour. Ladies wear woollen sari dhori full-sleeved blouse with a choli, chanli or shawl. This shawl is wrapped round the shoulders and its two ends are fastened together near the breast by means of a silver hook called digra. Women often wrap round their waist a scarlet coloured woollen or cotton cloth of about five to eight metres in length and about a metre in width. This is called gachhang.”

Another part of their life that the Kinnauris are fiercely proud of and protective about is their tradition of music. Though not much is known about the origin of Kinnauris as a peoples, they have found mention as ‘Kinners’ or ‘Kimpurushas’ (both roughly mean ‘is that a man?’) in most of our traditional Sanskrit texts. The Kinners — sometimes described as half-human and half-bird, and sometimes as a human with the head of a horse — were supposed to be the divine musicians and entertainers of the gods. In our myths, a Kinner is inseparable from his songs and his flute.

Kinners also had an unusual custom — polyandry — until very recently, though they have given it up now. Apparently Kinners trace this to Draupadi in the epic ‘Mahabharata’ who had five husbands. Apparently the five brothers and Draupadi spent a year hiding (agyatvas) in the region that is now Kinnaur (source: ‘Kinnaur in the Himalayas: Mythology to Modernity’).

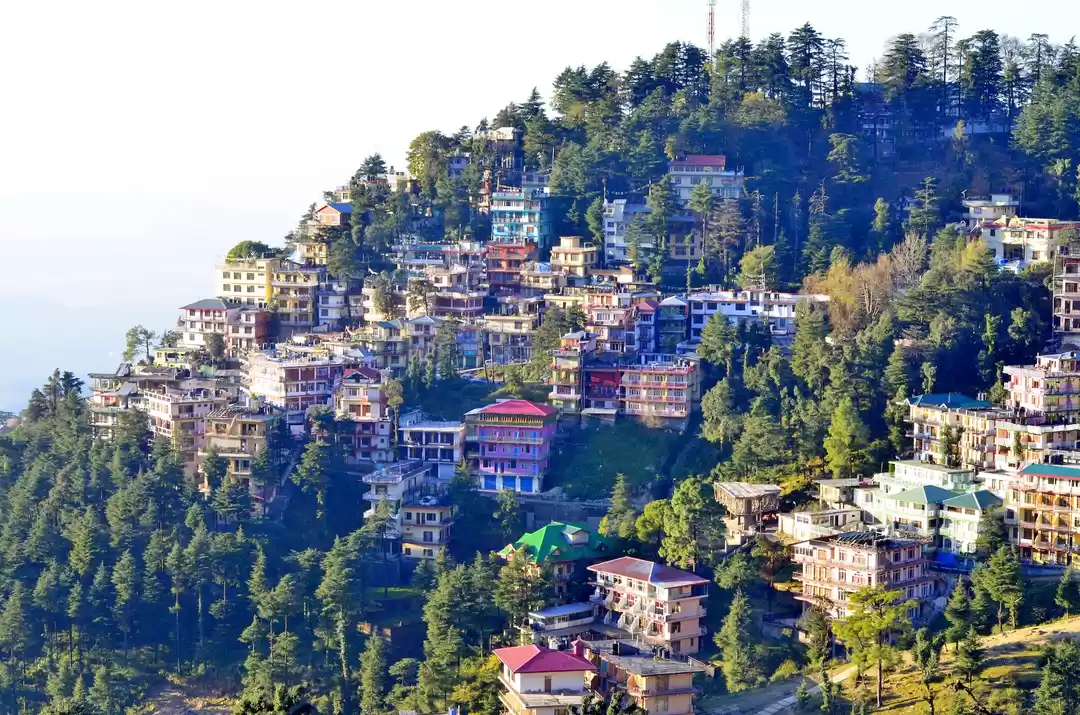

From our myths, Kinners are also supposed to be very pretty. It’s difficult to tell how they looked originally, but now they are a mixed race. Kinnaur is divided into three zones — upper, middle and lower. We were mostly in lower Kinnaur, just about touching the border with middle Kinnaur in Reckong Peo. Though people of lower Kinnaur are closer — both in terms of physical features and religion — to the people of Shimla district, those in the upper parts are said to be more like those in Spiti valley. The Tibetan influence there is apparent in physical features as well as religion. Not only does Buddhism gain prominence over Hinduism, some apparently even worship Bon deities — the traditional Tibetan religion that was replaced by Buddhism.

Personally, I thought even the people of lower Kinnaur looked very distinct from the people of Shimla or other parts of middle and lower Himachal. Whether it was the stone-crusher in Kalpa, the cultivator and the herdsman in Chitkul or the woman in Rakcham who walked past with her child on her back — they had distinct Mongoloid traces in their features. One unmistakable trace was the relief map-like creases on their weather-beaten faces — something that’s largely missing on those in Kullu and Mandi with the softer Punjabi-ish features.

We left Rakcham around 10am the next morning. It was a long 265-km distance to Kullu. We were to take an early-morning flight to Delhi and then connecting flights to our respective cities from there. It was after 8pm that we finally reached our hotel in Kullu. I don’t remember the name but it’s right next to Bhuntar Airport. In fact, the airport literally looks like the hotel’s backyard. The next morning, we walked to the airport from the hotel.

===================================================================

How to reach Rakcham: By road 230km from Shimla, 10km from Sangla, 265km from Kullu

Where to stay: Hotel Apple Pie, Hotel Rupin River View

Food: Vegetarian

Famous for: Not famous. It’s for solitude-seekers who look to escape the madness of ‘civilization’ for a few days and rest in the lap of unspoilt nature

Our Kinnaur road trip route: Manali-Sarahan-Kalpa-Chitkul-Rakcham-Kullu

Number of days: Four

Total distance covered: 660km

Contact number of driver for Kinnaur trip: Vinkal Hada (9459262520/9805473522)