Twyfelfontein, (meaning “uncertain spring” or “fountain of doubt”) is situated in the Kunene Region of north-western Namibia. Twyfelfontein consists of a spring in a valley surrounded by sandstone, which has hidden historic rock engravings all over the table mountain slopes. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) approved Twyfelfontein as Namibia’s first World Heritage Site in 2007.

Twyfelfontein lies within the Huab basin, part of an important ephemeral stream draining westwards to the Atlantic Ocean. When the hunter-gatherers lived in this area, the landscape looked very much as it does today; however the great sandstone formations on which the prehistoric artists carved their giraffes and kudu were formed over a considerable time span. Over millions of years, upheavals shaped this landscape: colliding continental plates pushed up mountains, glaciers carved out valleys, water covered the landscape for long periods, succeeded by massive outpourings of lava and the deposition of wind-blown sand, finally reaching it’s present state.

Twyfelfontein was not the only water source in the area on which these people depended. There are no records of the spring having ceased to flow at any time in the last 50 years, even though the spring appears to hold low water levels. The wind-deposited beds of Twyfelfontein sandstone provide the majority of the engraved surfaces. These surfaces are generally resistant to weathering.

In the 19th century, Wilhelm Bleek, Lucy Lloyd and Joseph Orpen began meticulously recording folklore and myths as told by San informants. Together with more recent testimonies by San of Namibia and Botswana, these accounts allow us to track a continuous, albeit fragile thread back through time to the makers of the southern rock art and their beliefs.

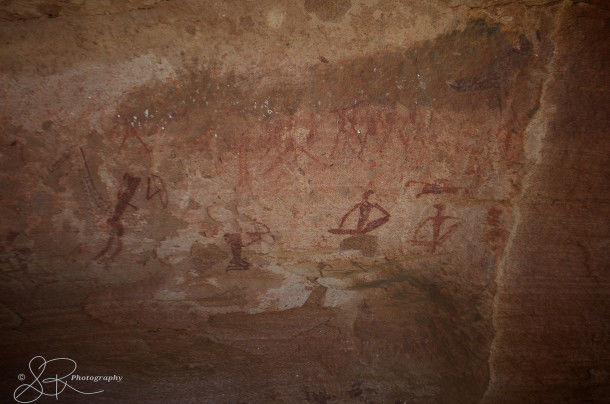

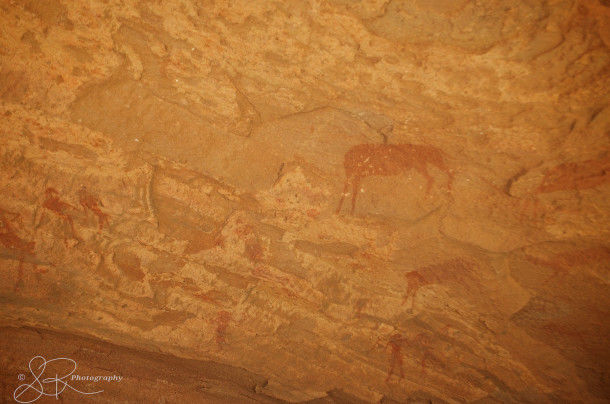

The Twyfelfontein area has been inhabited for 6,000 years, by the San people, also known as Bushmen. The group used it as a place of worship and a site to conduct shamanistic rituals. At least 2,500 items of rock carvings have been created during these rituals, as well as a few rock paintings.

The Dancing Kudu, when viewed from the right side, represents the transformation of humans into animals. The shaman, who in a state of ritual trance, has taken on the spirit of the animals.

Namibian rock paintings of the last 2000 years include fine and detailed examples using two or more colours, shading and complex overlays of images. While engraving techniques were relatively limited, their application at sites like Twyfelfontein shows advanced mastery of the medium surfaces were not only engraved by chipping at the rock with a pointed stone, or a hammer and punch, but were also ground or polished.

The carvings around Twyfelfontein represent animals such as rhinoceroses, elephants, ostriches and giraffes as well as depictions of human and animal footprints.

The Bushmen depended on the isolated spring during the dry months of the year when the shortage of water and food forced people to congregate there. The hunter-gatherers left behind large quantities of stone tools, fragments of bone and beads made from tiny discs of ostrich eggshells. The giraffe , being the tallest of the animals, was thought to reach up to the sky and help bring the rains.

The Bushmen used red rock, which they ground until it was fine, and then mixed it with fat to draw on the rock. This paint that they used withstands the rain and weather for very long periods of time. The Bushmen then used this paint in four different styles. These four style techniques are “monochromes, animal outlines in thick red lines, thinly outlined figures, and white stylized figures.

A.R. Willcox, writer of the article “Australian and South African Rock-Art Compared”, published 1959, says the tool they used to do these paintings was a brush made from animal’s hair or a single small feather. This may be one reason for the great fineness and delicacy of their painting.

A lot of rock art is actually in symbols and metaphors. Rock art gives us a glimpse of the Bushmen’s history, and how they lived their lives. Bushmen also used rock art to record things that happened in their lives. Bushmen also recorded “rain dance animals”. When they did rain dances (shamanistic rituals) they would go into a trance to “capture” one of these animals. In their trance they would kill it, and its blood and milk became the rain. As depicted in the rock art, the rain dance animals they “saw” usually resembled a hippopotamus or antelope, and were sometimes surrounded by fish.

The historical significance and stunning landscape of Twyfelfontein makes the site a fascinating stop. Although it’s location in far northwest Damaraland makes it a remote spot to visit, it should be included on any Namibian tourist’s itinerary.